Lian Langgang and The Rise and Fall of Bungan

This title (paper) has been presented at the 2nd International k@Borneo Conference 2021 organised by Pustaka Negeri Sarawak that has been held virtually on 14 and 15 September 2021. The presenter was Christine Horn from Digital Ethnography Research Centre, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia.

Abstract

In the 1950 in central Borneo a new religious belief system emerged a Kayan village in Indonesia and spread rapidly across the border to Sarawak. For converts, Bungan provided an opportunity to address complicated and often prohibitive rules and rituals around animal omens while maintaining links to the old adat and with it long established beliefs and traditions. But even though Bungan caught on quickly, it was also quickly replaced through fast spreading conversion to Christianity in the wake of Sarawak’s cession to British colonial rule. And yet, not everybody converted. In Long Moh, Lian Langgang, his wife and a few other Bungan believers continued to engage in rituals and ceremonies in a cautious co-existence with the Christian majority until Langgang’s death in 2019. The paper discusses interviews and videos with Lian Langgang taken some years before his death and reviews the rise and fall of Bungan not so much to record its practices and rituals but to consider what we can learn from its last adherents about identity, faith and culture.

Keywords

Bungan, Adat puun, Sarawak, Long Moh, Kenyah

Introduction

Religion, traditional practices and in material culture are closely enmeshed in most human societies. From this perspective, any major shifts in religion also often bring about a change in culture, leading to new practices but also to old ones being forgotten. A shift in religion is thus a major change in people’s way of life.

In this paper, I want to examine not just one such shift but several. In central Sarawak, in the beginning of the last century, most communities practiced what has sometimes been referred to as ‘adat,’ ‘adet’ or ‘adet puun’ or the old folk religion. This largely relied on animal omens but also on ritual practices carried out by religious priests or shamans.

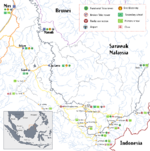

[Insert figure 1: Upper Baram and Long Moh]

In Sarawak, religious conversion was slowed by the Brooke’s opposition to the presence of missionaries in the interior. By the 1940s and 1950s, however, Christianity slowly spread in the region, partly coming from across the border in Kalimantan, where missionary activities were less strictly regulated (Harrisson, Tom, 1956). In addition, a new religion based on local customs and traditions spread among the communities in the area. It was called ‘Bungan’ or ‘Bungan Malan’ after its main deity.

The story of Bungan is that Jok Apoi in Uma Jalai, Long Abang in Kalimantan dreamt of a woman who taught him how, with the use of an egg, he could overcome the traditional prohibitions after observing a bad omen, thus neutralizing his bad luck (Prattis, 1963; White; B, 1956). Bungan is in fact fairly well documented, and a number of observers published their description of the origins of the faith and its practice (Aichner, P, 1956; Prattis, 1963; Tan Chee-Beng, 2016; White; B, 1956). According to Aichner, for example, the founder of Bungan, Jok Apoi,

…was a very poor man, always sick, consequently he could not look after his farm and of course poverty was his sad lot. One night he had a dream. Bungan (who is a female deity of the Kenyahs) appeared to him and told him to follow her advice. Then he would become healthy and prosperous. He had to do away with all the charms, he was not allowed to follow the pantang of his countrymen. If he wanted to obtain some favour from Bungan, he had to take an egg and curse with it all his enemies. He did all that; and he did get well, and his harvests were plentiful. (Aichner, P, 1956)

[[File::Bunganceremony.jpg|150px]]

Figure 2: Bungan ceremony in Long Sobeng, 1956, image copyright of the Sarawak Museum

Bungan spread quickly throughout the highlands. One picture from the Sarawak Museum archive, shows a Bungan ceremony carried out in Long Sobeng on the Tinjar in 1956. However, in many places it was soon replaced by Christianity, as a result of the British colonial government’s changed policies regarding the presence of missionaries in the interior (Harrisson, Tom, 1956).

Some of the names of these missionaries of the time, who brought Christianity to the region, are still well-known, such as Hudson Southwell, who co-founded the Borneo Evangelical Mission. The Roman Catholic faith also took hold in some communities, and Bungan all but vanished within a short period of time. But it didn’t vanish all together. Here and there, a few believers still remained who practiced their faith against the odds. This paper is about one such group and one man in particular: Lian Langgang in Long Moh.

Background

I met Lian first when I visited Long Moh during my work at Swinburne University in 2016. Councillor Simpson Njock who worked together with us on the research and who is from Long Moh introduced me to Lian during one of our fieldwork trips, because he knew that I was interested in Bungan and it’s material culture in particular. Councillor Simpson had taken part in Bungan rituals when he was growing up, and so he had some first-hand experience of Bungan practices. I had heard lots about the last Bungans in Long Moh, and about their church, and during several visits to Long Moh Lian was kind enough to show us around and explain some of the artifacts and the practices connected to them. In fact, Lian and his fellow Bungan believers were well prepared for visitors: A hand-written poster near their longhouse doors suggested the kinds of donations they expected from tourists for taking pictures and videos (see figure 3).

Figure 3: Fees for taking photographs or video of the Bungan believers and their artifacts

While Long Moh does not really receive a lot of visitors, this suggested that people were interested in the Bungans, and they frequently received requests to visit their place of worship. And indeed, Lian spent a generous amount of time showing us the different statues, drums, and the Orang Utan skulls that form the centrepiece of the Bungan religious shrine or place of worship at Long Kerang, just upriver from Long Moh. This paper and the presentation are based on this material, which includes pictures and videos of Long Kerang and of Lian Langgang, as well as several interviews in which Lian explains the way he and his fellow believers practice Bungan. Councillor Simpson kindly translated his words from Kenyah.

In addition to this, we also spoke to Pastor Christian Beh Gau in Long San, who had worked in Long Moh for eight years and who spoke about the way Christians and Bungans lived together in Long Moh. The interview with him was translated from Bahasa Malaysia by our research assistants. This paper, and conference presentation, are largely made up of their contributions. To start out, I will briefly review some of the literature on Bungan to provide an overview of the main concepts.

The Bungan religion in Long Moh

Bungan took up some of the beliefs of the old adat, as Lian Langgang explained:

We don’t actually believe in this omen already given by the birds, by the animals. Anyway, now we believe in Bungan only. We know about it though, [like for example,] the isit. We call it isit. If we go into the jungle and then see the bird fly from your right hand to your left, that one… Buen no nam leh… You go hunting you won’t catch anything. If it goes right to the left right in front of you. First if it goes to the left and it doesn’t come back again, it will make the sound ‘chit chit’, you cannot catch anything. But if the bird goes from your left to our right ‘chit chit chit’, then you’ll get, you’ll get [something]. That one is good. And then if it goes left after that, doesn’t matter, you still can get. That’s one… Nu chai ke badak... This one ‘tit tit tit tit’, this one is... There are so many things. That one says [that] you should not go. But if keyang… If the one ‘jiek jiek’ also [you won’t] catch anything, it will be raining also. We don’t believe but we understand the old adat, adet puun.

Lian also explained the difference between the adet puun and Bungan, in that Bungan believers used an egg to communicate to Bungan, the main deity:

Bungan... Bungan is the one not like the adet puun. So the adet puun, they use this eagle, they follow the eagle.. Plaki. But the bungan they don’t use the eagle, plaki. [Bungan uses the] egg. Padau. They use this padau to become messenger. To talk to Bungan. Padau is specifically the name of the egg when they use it to go and talk to Bungan Malan. It is a normal egg, they call it padau.

Reports from observers in the Sarawak Government at the time when Bungan first spread in the region also touch on this. A. M. Phillips, a district officer at the time, noted:

When a person “masok Bungan” it is not that he does not believe there is no power in the old spirits and pantangs [prohibitions] but that Bungan will protect him from them” (Phillips, 1956, p. 229)

What was Bungan?

Observers at the time, in particular the British government servants who contributed to the literature on Sarawak during the time, suggested that Bungan’s success was related to it being based on local social and cultural practices, but also that it used some of the strategies implemented by Christian missionaries. According to Tom Harrisson’s notes about Bungan, it was also a contestation of local ways over the religion brought by the outsiders:

“Bungan Malan is a new cult or „religion” that now probably commands the more or less allegiance of more people than any one interior Borneo Christian sect. I first met with it in the upper Baram in 1949. Since then it has spread tremendously, largely in secret, always subtly, and always behind the missionaries – behind, that is, in the temporal sense; against them in the moral… That is the positively “pagan”, endemic side of Bungan, preservation of the past general approach, centred into a unified, local ”native” leadership both on earth and in air (dream); but without all the past trappings. For the past trappings were already vanishing when goddess Bungan’s word came to Jok Apoi by night. The missions were earlier off the mark, over the border. The Dutch, who previously administered that side, regulated them but did not severely restrict their rope in the Brooke way. So they had got far by 1940, where nothing was yet impacting in Sarawak. This was essential base for Bunganism.” (Harrisson, 1956, p. 147)

According to Harrisson, Bungan’s success was related to the way it included elements that were important in practical terms, such as keeping pigs under the longhouse or not having to pay fees, but it also enabled them to practice their traditional culture including telling old stories or singing traditional songs. Harrisson also emphasized an element of identity as the key to Bungan’s rapid uptake in the region:

“Bungan teaches:

- you can work every day, if you like, including Sunday;

- You need not give up drinking, smoking or keeping pigs under the house;

- You can believe (most of) the old legends, sing the old head songs, etc.;

- You do not have to give fees to the teacher, tithes to the mission, offerings to or in the church;

- You need offer no submission (beyond the demand of customary goodmanners)to any sort of out-sider […];

- You can be proud of being yourselves, orang ulu only;

- You are independent of any beliefs and rituals introduced by white men. “ (Harrisson, 1956, p. 147)

Figure 4: Bungan statues near Long Karieng

Religious conversion in the Ulu

Harrisson, was sure that Bungan had picked up some of the proselytizing strategies of Christian missionaries in the region, but not all contemporaries agreed that Bungan was a reaction to, or even a contestation of the incursion of the Christian faith. What was true, however, was that Bungan was much more lenient in terms of preserving some of the traditions and the material culture of the old religion, including carvings and statues, and rituals involving reference to the old headhunting days, as we will see below. At the same time, the way that different faiths spread throughout villages in the region often meant that one village, sometimes even one longhouse, could be split into two or even three different faiths, as Lian Langgang explained

Bungan, come from Long Nawang. [The people from] Long Nawang brought Bungan to Long Moh [while we were] at Long Kareng, Before we built this longhouse. When I was very young, still running naked. At the time, half of the people were bungan, half of the people adat puun. When Long Kareng moved to Long Moh some people still use the old adet, and some already believed in bungan. Setengahsetengah. When Bishop Kelvin brought Christianity to Long Mo [the community was] divided into three. One bungan, one is the adet puun and some Christian. In Long Kareng, that was the old longhouse there before. Long Kareng, some converted already to Christianity then when come to Long Mo, more people converted to Christianity.

Pastor Gau also confirmed this, mirroring Lian’s suggestion about how the conversion of the village took place. According to him,

Somewhere after the 1940s [people converted to Roman Catholic]. Before that, Long Mo’ was under SIB…Because the pastoring area for the Pendita was too big, he gave Long Mo’ to the Catholics. That’s how the Catholics take in charge… According to the history, SIB came first in Long Mo’ and Long Sela’an actually, under the Pendita Hudson. But after he found out that the pastoring area was too large, he focused on Lio Mato, Long Jaik, Long Mekaba… That’s why there’s a lot of SIB church in Lia Mato and Long Jaik, as what people call as Lepo Agak. There is no Catholics.

This suggests a respectful and tolerant approach to religious conversion that was also mirrored in Lian’s attitude towards the conversion of his own children:

Those who convert to Christianity we just let them do it, we cannot say no to them because everyone has their own right to choose what their belief is. I believe in Bungan, if I die, that’s the end of it. That’s my opinion. I won’t say no, I won’t say yes, it’s up to people to choose their religion. Now like for us, me and my wife, and there’s another uncle again and the wife. Mostly husband and wife, husband and wife only. Everyone else, the children converted to Christianity already, most of them…. At the moment there are nine people, just four couples and then one single.

Pastor Gau also suggested that the children of the Bungan believers had already converted and that it was only their parents who were holdouts in the village.

[The children of the Bungans,] most of them are SIB. Only their parents still practice Bungan. And if their parents died, I don’t think they will follow it anymore. That’s why I thought it takes time to persuade the elders to change their mind. Because they are deeply rooted with the Bungan belief, if we just leave them, how will people see us? They won’t accept us because they think we have no stand. [Their children,] sudah lama, quite some time already… They changed their mind when they compared their parents’ beliefs with Christianity. So they decided to be baptised and they’re the ones who mostly joined the SIB church in Long Mo’.

Figure 5: Orang Utan skulls in the Bungan place of worship

Bungan Mamat

I will now review some of the traditional practices that were the centre of Bungan belief in Long Moh. According to Lian Langgang, religious practice in Long Moh revolved around the annual Mamat celebrations.

Every year we celebrate mamat. [There are two,] one smaller mamat before paddy harvesting, and then mamat biok is the bigger mamat, that is after harvesting. The bigger mamat they have perahu, you know the drum that hangs [in their church]. They play that whole night. So during the mamat biok, they perahu. Perahu means they celebrate the whole night and then comes to three o’ clock they start playing the drum. Once they start play the drum, betutu they call it, betutu letaan, that’s the beat of the drum and they do, they start at 3am and they will do it until dawn, in the morning.

When it’s’ mamat the place [where it is celebrated] is near the place of worship. When people go there, they make a wooden [statue], they make the eyes, the nose, the mouth... But it is just a small piece like this only, just like a head. So they talk to... berbungan with the padau, to the head. They pretend that they go headhunting so they hide [the head] there, then they do all the rituals, talking, talking... After that, they will go back to see the head, the wooden head that they made. ‘Oh, it is sleeping’ they say. ‘Tidur dia’. Dia cakap bungan sudah bikin dia tidur [Bungan made him fall asleep]. They will go and use their spear, and spear it... After that they bless a lot of things, bless Bungan, they bless their gun, spear, and they bless the tanah [earth]... They will sing the whole night, they will sing. And they will dance [and play] the drum. Jatong do main nang nah….

[After they are done with the wooden head] they come back… when it comes to night-time like around 8 or 9pm, then they will go and tune their jatong. The drum, they call it jatong… After that, they wait, so those who want to dance they dance to the sape music, they just dance like if they do the mamat here then they put the jatong at this side here, far end here. So that people would dance that side. So when come to three o'clock just now, then they start to play the drum already. So when they do that, after they do that they do the dayung. And when in dayung they go into trance for that night… and one whole day, starting from the night…

Tradition, Ritual and Religion

Even though Bungan removed many of the pantangs that made daily life difficult, many elements of the old traditional culture were maintained. Christianity had a more complicated relationship with material culture, as Pastor Gau explained:

According to most of the church elders, whatever musical instrument that was used in the old beliefs should not be used again. [Personally I think that, while] we can’t change the music [that is played in the church], but if we use the musical instruments like the jatung utang to praise God, [in my opinion] that is not wrong actually. But some [people] say that the things that we used in the old religion before cannot be taken into Christian practice. [I think that] even the usage of Sape’ is not wrong, but some argue that Christians should not bring Sape’ into the church.

Pastor Gau also explained his way of thinking about material culture that relates to old traditional beliefs:

For me personally, each pastor has their own way to preach people about Christianity. Once people brought me a tajau which has dragons’ motif on it. Of course, I feel bad if I threw if I threw it away, but for our faith, let it go… I think our thoughts and beliefs that should be changed. Because back then, the tajau is used to keep bad things. Someone told me before that he took a bear’s head for decorating purposes. “Can I do that pastor? I just want to use it as decorations”. I answered, “There’s no problem if you took it for decorations, but if you took it with the intention to worship it then it is wrong because that thing is powerless”. The same thing goes with the orang utan skull. It is just a skull. But when we believe in the skulls’ so-called power, then the Devil will take advantage and make it seems like the skull has powers. This will affect our faith…

At the same time, the pastor also understood that some of the old beliefs were deep rooted and people were not always ready to let go:

There are some who still [believe in rituals]. Especially during the farming time. Based on my experience in Long Mo’, there are some who also believed in spirits that can [come to] their farms... For example, during the rice harvest, they sometimes pray. For us Christians, that is not a problem. But some of them, even after they prayed, the do other things like inserting chillies or garlic into the rice husk, saying that it will make the rice spicy to eat… Sparrow, monkeys and others. Even though those are the things that we can eat, but if we believe in it, it might influence our life too. Therefore, as a Christian, we should not believe in those kinds of things anymore.

These comments suggest that the pastor was aware of the intermingling of old beliefs and new religious ideas, and the ongoing struggle to separate out one religion from previous ones.

Religion and Material Culture

Pastor Gau’s remarks as well as Lian’s contributions point to the role of material culture in religion, and points to the cultural loss that occurs as a result of religious conversion. Not only are old practices replaced by new, a rich body of artifacts and the related skills and practices are lost as new religious beliefs take over. However, Lian had held on to many practices and had even continued these throughout the years in which he and his fellow Bungan believers were relatively isolated in Long Moh. For example, with regards to the protective statues around the Bungan place of worship, Lian explained:

One of the statue in that case you see the one the house here, when you come up this side there are some there, and then that two they call it uyat atep, the atep statue, that is to protect the people. This is for protection like security, security guard (laugh). They are left handed. Benu na kabieng? Left handed, he assume that those left handed, nobody can go against that. Even if they come in trance, in the dayung, they pull their parang lefthanded. That is the security. This particular security guard, the deity of the security, then they come into the person who go into trance, it will always recognise it by the way it holds its parang. He will be left handed. The other statue, after that, inner a bit, this is the one that protect them from sickness. They make the statue like this. This is the tree, they make the statue, the head, the eyes, the mouth, under the tree. Underneath like that. Not like this, not here. At the side. So that one is to protect from sickness.

Figure 5: Statues near the Long Karieng place of worship

Conclusion

These comments and contributions give some indication of the ongoing relevance of old beliefs, but also about the way that material culture is entangled with religious practices. Indigenous knowledge, in its many embodied and experiential forms, is also embedded in these practices and material objects. My conversations with Lian provided some glimpses of this wealth of knowledge that the Bungan believers had continued to preserve, and regularly renew through their rituals and celebrations. This paper aims to share some of this information, but also to suggest the precious and ephemeral nature of this knowledge, as it fades away with the people who hold it. I hope that sharing these excerpts here may encourage those who know any of the remaining Bungan practitioners to engage with them and with their knowledge of the old beliefs, traditions and practices in a more comprehensive and organised way.

Acknowledgements

The research as part of which the data for this paper was collected was carried out by researchers at Swinburne University of Technology in Kuching, Sarawak (Malaysia), and in Melbourne, Victoria (Australia), with funding provided by both campuses (Malaysia and Australia). The Melbourne-based project team included Professor Jane Farmer, Professor Sandra Gifford, Dr Christine Horn, and Dr Christina Ting. The Sarawak-based project team included Dr George Kwang Sing Ngui, Mr Gregory Lik Hoo Wee, Dr Bertha Chin, Ms Raine Melissa Riman, Associate Professor Marc Weng Lim, Mr Wilson Moses Suai and Mr Simpson Njock Lenjau. Thanks to Ms Liss Ralston for statistical assistance, and research assistants Ms Patricia Nayoi, Ms Aurelia Liu Mei Ying, and Ms Adeline Lenjau. We would like to acknowledge the contributions of the ketua kampung and people in Long San, Long Silat, Long Mekaba, Long Jeeh, Long Moh, Long Sela’an, Long Semiang, Long Tungan, Lio Mato and Long Banga, and other villages we visited. Ethics approval was granted by the Swinburne University Human Research Ethics Committee.

References

- Aichner, P. (1956). Adat Bungan. Sarawak Museum Journal, 7, 476–477.

- Harrisson, Tom. (1956). Ulu Problems. The Sarawak Gazette.

- Prattis, I. (1963). The Kayan-Kenyah Bungan Cult. Sarawak Museum Journal, 11(21–22), 64–87.

- Tan Chee-Beng. (2016). It Is Easy When You Are a Christian: Badeng Kenyah Conversion to Christianity. Journal of Cultural and Religious Studies, 4(4). https://doi.org/10.17265/2328-2177/2016.04.004

- White; B. (1956). Bungan: A New Kayan Belief. Sarawak Museum Journal, 7, 472–475.